Segregation has been illegal in the United States for decades, but many neighborhoods are unofficially segregated – and separate is not equal. Majority-Black areas of American cities and towns are overwhelmingly less desirable and less prosperous. The built landscape of the United States reflects a legacy of place-based racial inequality influenced by housing and urban development policies of the 20th century.

The economic prosperity experienced by most of America during and after World War II never really reached Black Americans. Federal financial assistance programs like the 1944 G.I. Bill helped many returning veterans buy homes, start businesses, or attend college, but racial discrimination in government and business meant Black Americans were left behind in the resulting housing boom. While white Americans flocked to subsidized homes in newly created suburbs, many people of color had to remain in cities with dwindling jobs, overcrowded housing, escalating poverty, and declining property values. They were restricted to specific neighborhoods formally, through discriminatory property owner policies and zoning laws, and informally, through racist mob violence.

Place-based inequalities were exacerbated later in the 20th century, when urban renewal and public works projects decimated poor neighborhoods and displaced their mostly Black residents.

Federal urban renewal programs from the 1950s to the 1970s displaced more than 300,000 families across the country, disproportionately razing Black neighborhoods in favor of commercial and industrial development. Any housing created by these projects was in smaller quantities and less affordable than before, or difficult to obtain without political connections, meaning most residents were forced to leave.

In Cleveland, 84 percent of those displaced by urban renewal were families of color, while in Minneapolis, families of color were just three percent of the overall population but 29 percent of those displaced. Black families across the country lost their homes, jobs, businesses, and social networks, leading to concentrated poverty and increased overcrowding in remaining residential areas. The economic and psychological toll was devastating.

Interstate highway construction also began in the 1950s, prioritizing the needs of white suburban commuters over urban residents. New highways destroyed or isolated many Black neighborhoods, cutting them off from schools, stores, and economic opportunities. In some cases, as laws prohibiting housing discrimination were passed, segregation was built into the physical environment through strategically placed roads. Exhaust fumes and road runoff polluted the neighborhoods closest to highways, causing additional harm to their residents.

Understanding the historic development of spaces where people live and work is vital to understanding inequality in America. Racism, especially anti-Black racism, is threaded through the historical decisions and policies that shape life today.

The resources collected here document the historical dimension of race, space, and design, as well as propose equitable paths forward.

Explore a curated sample of Harvard research and resources related to anti-Black racism in space and design below.

Read

The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects

Where you live impacts future success. This economic study of more than 7 million families in the United States shows that the neighborhoods in which children grow up shape their earnings, college attendance rates, and fertility and marriage patterns.

The Just City Essays: 26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

In this collection of essays architects, mayors, artists, doctors, designers, scholars, philanthropists, ecologists, urban planners, and community activists explore strategies for creating more equitable cities that improve quality of life and livelihoods for urban residents.

Stephen F. Gray: "We have a name for the uneven distribution of exposure and risk along racial lines, and it’s not COVID-19. It’s structural racism."

Black and brown Americans have died at disproportionately high rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. This article lays out the components of structural racism contributing to these rates and proposes policy changes in economic development, housing, and public domain infrastructure to address inequality.

A Shared Future: Fostering Communities of Inclusion in an Era of Inequality

What would it take to meaningfully reduce residential segregation and mitigate its negative consequences in the United States? In this volume, leading academics, practitioners, and policymakers examine different aspects of the complex and deeply rooted problem of residential segregation and propose concrete steps that could achieve meaningful change within the next ten to fifteen years.

Building Boston, Shaping Shorelines

This online exhibit illustrates the building of land in Boston through historic maps. Maps from insurance companies and the Boston Redevelopment demonstrate the sudden and dramatic reordering of urban spaces for urban renewal that led to the destruction and displacement of many communities.

Erich Lindemann papers

Erich Lindemann (1900-1974) was a Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Associate Professor of Mental Health at Harvard School of Public Health known for his work in preventive intervention, particularly with subjects of grief, loss, and other forms of crisis. This archival collection includes Lindemann’s study of the effects of loss and disruption on the displaced families of Boston’s West End redevelopment, which was used to inform later urban redevelopment projects across the nation.

Jonathan R. Beckwith papers

Jonathan Beckwith (born 1935) is the American Cancer Society Research Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics at Harvard Medical School. Beckwith was Faculty Sponsor of Harvard University’s Campus Tenant’s Support Union (circa 1969-1975). This archival collection documents local community resistance to the expansion of Harvard Medical School into residential areas of Roxbury, Massachusetts including materials from the Roxbury Tenants of Harvard campaign.

Watch

Racial Inequity and Housing Instability in Boston: Past, Present, and Future

Millions of Americans have long struggled to pay for housing, with communities of color additionally burdened by housing discrimination and historical race-based policies. In this panel experts explore the housing affordability crisis for people of color in Greater Boston as well as the long history of community activism in the area.

Listen

Beloved Streets Podcast: Bridgette Wallace, G|Code House

In this podcast Bridgette Wallace, founder of G|Code House (a placed-based community coding program for young women and non-binary people of color in Roxbury, Massachusetts) discusses incorporating education, empowerment, and community justice in addressing geographic and demographic inequities.

Nexus Podcast: De Nichols

In this podcast activist and social practice artist De Nichols discusses the #DesignAsProtest movement, alternatives to profit-driven models of practice for designers, and the importance of self-care and collective care in the face of the white supremacist logics that linger in design culture.

Citations for Section Overview

- Archer, Deborah N. 2021. “Transportation Policy and the Underdevelopment of Black Communities.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3797364. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3797364.

- Armborst, Tobias, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore, and Riley Gold. 2015. “Blood, Shed, and Fears: The Resiliency of Racism.” Interboro. 2015. http://www.interboropartners.com/projects/blood-shed-and-fears.

- Blakemore, Erin. n.d. “How the GI Bill’s Promise Was Denied to a Million Black WWII Veterans.” HISTORY. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/gi-bill-black-wwii-veterans-benefits.

- Budds, Diana, and Diana Budds. 2016. “How Urban Design Perpetuates Racial Inequality–And What We Can Do About It.” Fast Company. July 18, 2016. https://www.fastcompany.com/3061873/how-urban-design-perpetuates-racial-inequality-and-what-we-can-do-about-it.

- Digital Scholarship Lab, “Renewing Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed April 6, 2021, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram&text=about.

- King, Noel. 2021. “A Brief History of How Racism Shaped Interstate Highways.” WBUR News. April 7, 2021. https://www.wbur.org/npr/984784455/a-brief-history-of-how-racism-shaped-interstate-highways.

- Lee, Jr., Bryan. 2020. “America’s Cities Were Designed to Oppress.” Bloomberg.Com, June 3, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-03/how-to-design-justice-into-america-s-cities.

- Nelson, Robert K. 2020. “Mapping Inequality: There Were No Dog Whistles, the Racism Was Loud and Clear. » NCRC.” September 10, 2020. https://www.ncrc.org/mapping-inequality-there-were-no-dog-whistles-the-racism-was-loud-and-clear/.

- Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How our Government Segregated America. Accessed April 5, 2021. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990149136710203941/catalog

- Rothstein, Richard. 2014. “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of Its Troubles.” Economic Policy Institute (blog). October 14, 2014. https://www.epi.org/publication/making-ferguson/.

- Solomon, Danyelle, Connor Maxwell, and Abril Castro. 2019. “Systemic Inequality: Displacement, Exclusion, and Segregation.” Center for American Progress. Accessed May 19, 2021. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472617/systemic-inequality-displacement-exclusion-segregation/.

- Vey, Hanna Love and Jennifer S. 2019. “To Build Safe Streets, We Need to Address Racism in Urban Design.” Brookings (blog). August 28, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/08/28/to-build-safe-streets-we-need-to-address-racism-in-urban-design/.

Citations for Images

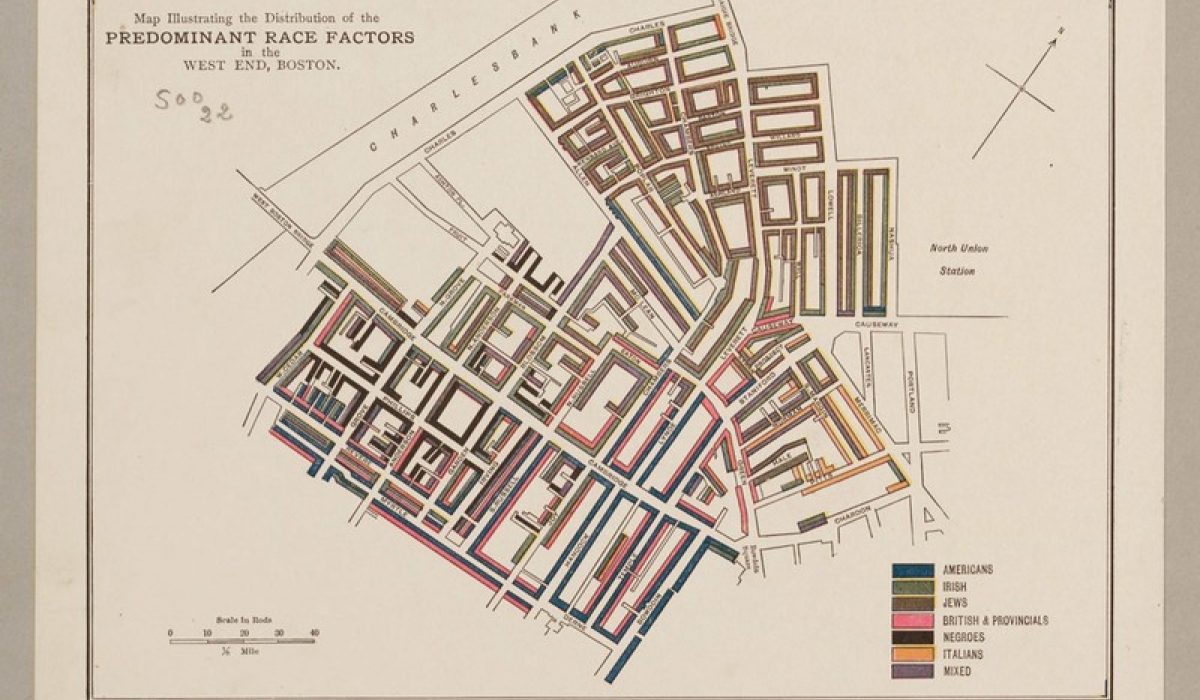

- Map Illustrating the Distribution of the Predominant Race Factors in the West End, Boston, circa 1903 | Unidentified artist. Social Settlements: United States. Massachusetts. Boston. South End House: South End House, Boston, Mass.: From "Americans in Progress.": Map Illustrating the Distribution of the Predominant Race Factors in the West End, Boston, circa 1903. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Transfer from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Social Museum Collection. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/HUAM57824soc/catalog

- Housing complex protest against highways in Cambridge, MA, 1960 | Protesters hanging banners at housing complex, Protest against Highways. North Harvard. (1960), Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD5101mc.0701), Source unknown. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork286988/catalog

- Highway in Detroit, MI, 2014 | MacLean, Alex S. Detroit, 2014. Detroit, Wayne, Michigan, United States. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design (190231). http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/8001310899/urn-3:GSD.LOEB:27348624/catalog